Ever since the great financial crisis of 2008, investing has been easy. Since January 1, 2009, the S&P 500 has returned 15.0% and the Bloomberg US Aggregate Bond Index has returned 4.2%, annualized. 1 Anyone holding a 50/50 portfolio of stocks and bonds during that time would have received an annualized return of 9.6%!

With the S&P 500 setting record highs and interest rates dropping to all-time lows, are recent returns likely to persist? Each year, JPMorgan publishes capital market assumptions designed to “aid investors with strategic asset allocation…over a 10- to 15-year investment horizon.”2 For 2021, JPMorgan is assuming a 4.1% return for U.S. large cap equities and a 2.1% return for U.S. Aggregate Bonds. These figures suggest that a 50/50 portfolio would return approximately 3.1%, annualized, over the next 10–15 years. That would be a huge disappointment when compared to the 9.6% realized since 2009. Would such a modest return even keep up with inflation? What should a wise investor do now?

In this paper, we examine the two traditional, investable asset classes and the need for a third true alternative asset class. Then we recommend that investors include hedge funds in their portfolio to further diversify the source of returns, adding stability to the portfolio and thus improving the portfolio’s risk-adjusted rate of return.

Investable Asset Classes

We can generalize the investment world as having two main asset classes—fixed income and equity— defined by the primary risk they take:

- Fixed income (credit risk free) is an investment that earns a contractual rate of return depending solely on the lending period (i.e., the interest rate risk). Interest rate risk is tied to the duration of the contract, and returns typically increase as the duration increases (i.e., as interest rate risk increases).

- Equity is the ownership of any residual value after all liabilities are repaid, and its return is tied primarily to market growth (i.e., the market risk).

All other factors being equal, if you anticipate market growth, equities should provide a positive rate of return. This makes sense, given that equities are nothing more than the leftovers. If the market grows and liabilities are fixed, then market growth leads to more leftovers. On the other hand, if you anticipate that the market will shrink, the contractual rate of return of fixed income should be more attractive.

Thus, traditional portfolios are composed of these two traditional asset classes, each providing a positive rate of return but performing better under different market conditions (i.e., growing markets versus receding markets). They have worked well together historically, but they may not provide the portfolio stability going forward. The problem in today’s market environment is that both asset classes have low expected future returns and may be correlated to one another due to artificially low interest rates.

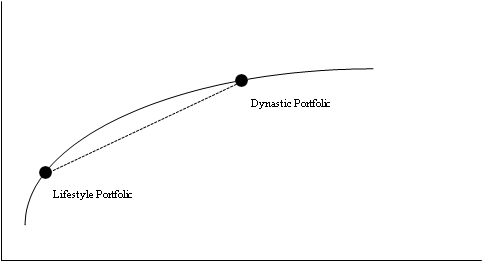

In a world in which we use only these two investable asset classes, investment asset allocation is challenging under the current circumstances. For example, how can anyone allocate money to fixed income with an expected return of only 2.1% and significant downside risk if interest rates rise? Ideally, we would have a third option: an investable asset that derives its return from an alternative, uncorrelated source of risk. The addition of such an asset to the portfolio can improve the risk/return dynamic. We need an investment that is not highly correlated with interest rates or the equities markets, but rather has an independent return, a.k.a. an “alternative asset.”

Alternative Investments

It seems everyone is selling alternative investments these days, but what is an alternative?

- An alternative is an asset or strategy that provides a return unexplained by the price movements of equities and fixed income (a.k.a. equity market returns, or “beta”). It is often the result of one’s ability to identify and capture mispricings in the market or securities (i.e., “alpha” risk).

To be a good diversifier, an alternative investment must generate its return from something other than interest rate risk or market risk. In the world of high finance, a return not explained by interest rates or equity returns is called “alpha.” Thus, the true benefit of an alternative asset is the unexplained return (alpha) it provides.

Many of the most commonly offered “alternatives” are nothing more than substitutes for their public and more liquid brethren. Private equity, for example, is nothing more than an equity investment in a non-publicly traded company. Do private equity returns produce alpha? Yes, investing in private companies has historically yielded greater returns than those predicted by the market risk factor. However, a significant portion of private equity returns are simply levered equity market returns. Thus, it is more accurate to include private equity as a replacement for some portion of the public equity allocation than to view it as a true alternative asset. The same can be said for private real estate, private lending, etc.

Few alternative investments generate mostly alpha returns. Fortunately, we have a valuable alternative for adding alpha to a portfolio: hedge funds.

Hedge Funds

“Hedge fund” is the generic term applied to a private fund that produces returns via trading strategies or investments in securities. The basic characteristics of a hedge fund include the following:

- A private partnership structure

- A defined liquidity structure (usually quarterly)

- A fee structure that includes a management fee (typically 1.0–2.0%) and an interest in the profits (typically 20%)

There are many hedge fund strategies, and their returns are derived from different proportions of market, interest rate, and alpha risk. Exhibit 1 briefly describes the most popular hedge fund strategies. Creating a true alternative asset class for a portfolio would require distilling a portfolio of alpha- generating strategies. This is easy to understand but difficult to do in practice, largely due to the common criticisms of hedge fund investing discussed below.

Criticisms of Hedge Funds

Hedge funds are subject to four common criticisms:

- High fees

- Complex structures

- Lack of full investment transparency/attribution

- Limited redemption availability

High fees are the most contentious argument against hedge fund investing. If you can inexpensively replicate the returns of hedge funds, then this argument holds weight. For example, many long/short equity hedge fund portfolios are net long equities resulting in returns driven primarily by equity market returns. It is certainly less expensive and easier to access market returns via an equity index fund or exchange-traded fund than via a hedge fund—but hedge funds provide a less expensive way to access alpha.

Research has shown that, on average, long-only equity managers underperform3,4,5 largely because they cannot generate excess returns after fees. Therefore, simply gaining exposure to the market return as inexpensively as possible is a preferred strategy for long-only equity investing. However, alpha returns are not market returns. Alpha returns are generated purely through the manager’s ability to generate returns not explained by the market. Thus, the fees paid to hedge fund managers should be compared only to the alpha they generate.

Consider this example: A hedge fund provides an 8.0% gross alpha return and charges a fee of 2.8%, thus netting a 5.2% alpha return. In this scenario, an investor is paying 2.8% for 5.2% of alpha, or roughly $1.00 for each $1.86 in alpha return. That math works.

Some may wonder, “Why would I pay 2.8% for a 5.2% net return when I can just invest in the SPY, earn 15%, and pay only 0.09% in fees?” But the logic is flawed as that analysis compares apples to oranges. The SPY doesn’t create any alpha return and is set up specifically to provide the equity market return.

To compare these two strategies, let’s assume SPY has a positive net alpha return of 0.01%. Using the same math as before, spending 0.09% to generate 0.01% of net alpha return means you pay $9.00 for each $1.00 of alpha return. In this example, we’re comparing apples to apples, and hedge funds appear less expensive than index funds. However, we must use hedge funds correctly for this to be a valid comparison.

The hedge fund world is broad and often opaque, leading us to the second criticism of hedge funds: their complexity. Indeed, hedge funds are complex, and understanding their trading strategies may require an advanced degree. This complexity may be a good argument against investing directly in hedge funds, but it is not a good argument against the hedge fund asset class. Professional management of a portfolio of hedge funds can provide the due diligence needed to mitigate the risk associated with the complexity of hedge funds. For this reason, many hedge fund investors rely on a professional allocator or a fund of funds to build a portfolio of hedge funds.

The third criticism of hedge funds focuses on their lack of transparency. Many hedge funds conceal their investments for competitive reasons, thus complicating oversight. However, large pools of capital are able to dictate terms around transparency and other factors, thereby receiving enough information to manage risk exposure. Such leverage is usually driven by the sophistication of the investor and the size of the investment (i.e., the larger the investment, the more likely the investor can dictate terms).

Limited liquidity is the fourth and final common criticism of hedge funds, but it is overcome through diversification. Redemption periods vary across funds and strategies; therefore, this risk can be managed by maintaining a fully diversified portfolio in which other sources of liquidity are available.

This review of the common criticisms of hedge funds reveals that a certain level of expertise and access is not only valuable but also required to build an effective, alpha-focused hedge fund portfolio.

The Best Way to Access Hedge Funds

The best way to access a diversified hedge fund portfolio is to secure the services of a professional to build a portfolio via direct investment (usually requiring a minimum of $50 million) or via a professionally managed fund of funds. A fund of funds is often criticized for layering fees on fees. However, professionals merit their fees; their ability to aggregate larger pools of capital and negotiate better terms may actually lower the cost of the underlying funds.

Given the forecasted low returns of stocks and bonds, the current market presents an opportune time to invest in hedge funds. When the two traditional asset classes are expected to provide low future returns, it makes sense to pursue hedge funds as a valuable alternative. Yet at the end of the day, it doesn’t matter how well the traditional asset classes are performing. Hedge fund performance is independent of them. Therefore, most qualified portfolios can benefit from the addition of well- selected, well-managed hedge funds.

Summary

Alternative assets represent a broad category of investments, and hedge funds are the best alternative for adding a truly unexplained source of return. Building a portfolio of hedge funds can distill the overall return primarily to “alpha”—a return not explained by interest rate or equity market risk. Adding alpha to a portfolio can further diversify the source of returns, adding stability and thus improving the portfolio’s risk-adjusted rate of return.

In today’s market environment with the S&P 500 setting record highs and interest rates dropping to all- time lows, adding an uncorrelated source of return in the form of hedge funds is not only prudent, but also necessary. Given the complexity of hedge funds, leveraging a professional is the best strategy for adding them to any investment portfolio.

Endnotes

- Annualized returns from January 1, 2009, through December 31, 2020.

- JPMorgan. (2021). Long-Term Capital Market Assumptions Matrices. Retrieved from https://am.jpmorgan.com/content/jpm-am-aem/emea/ch/en/adv/insights/portfolio- insights/ltcma/matrices.html.

- Jensen, Michael C. (1968). The Performance of Mutual Funds in the Period 1945-1964. Journal of Finance, 23, 389–416.

- Malkiel, Burton G. (1995). Returns from Investing in Equity Mutual Funds 1971 to 1991. Journal of Finance, 50, 549–572.

- Carhart, Mark M. (1997). On persistence in mutual fund performance. Journal of Finance, 52, 57–82.

Disclosures:

This information is provided, on a confidential basis, for informational purposes only and does not constitute an offer or solicitation to buy or sell any security. It is intended solely for the named recipient, who, by accepting it, agrees to keep this information confidential. An offer or solicitation of an investment in a private fund will be made only to accredited investors pursuant to a private placement memorandum and associated documents. There can be no guarantee that a client will achieve the intended investment returns or objectives. There are associated risks with all investments and those risks are described in the investment advisory agreement. The information contained in this material does not purport to be complete, is only current as of the date indicated, and may be superseded by subsequent market events or for other reasons. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. Autumn Lane Advisors, LLC is not a law firm, CPA firm, or insurance agency and does not provide legal advice, tax advice, or insurance products.

© 2020 Autumn Lane Advisors, LLC. All rights reserved. This material may not be reproduced, displayed, modified, or distributed without the express prior written permission of the copyright holder. Send email requests to info@autumnlanellc.com.